United States Farmland Faces Water Crisis as Ogallala Aquifer and Central Valley Groundwater Rapidly Decline

UNITED STATES — One of the most serious and long-term threats facing American agriculture is no longer just drought, but the rapid depletion of groundwater combined with the collapse of farmland’s natural ability to capture and recycle rainwater across key food-producing regions.

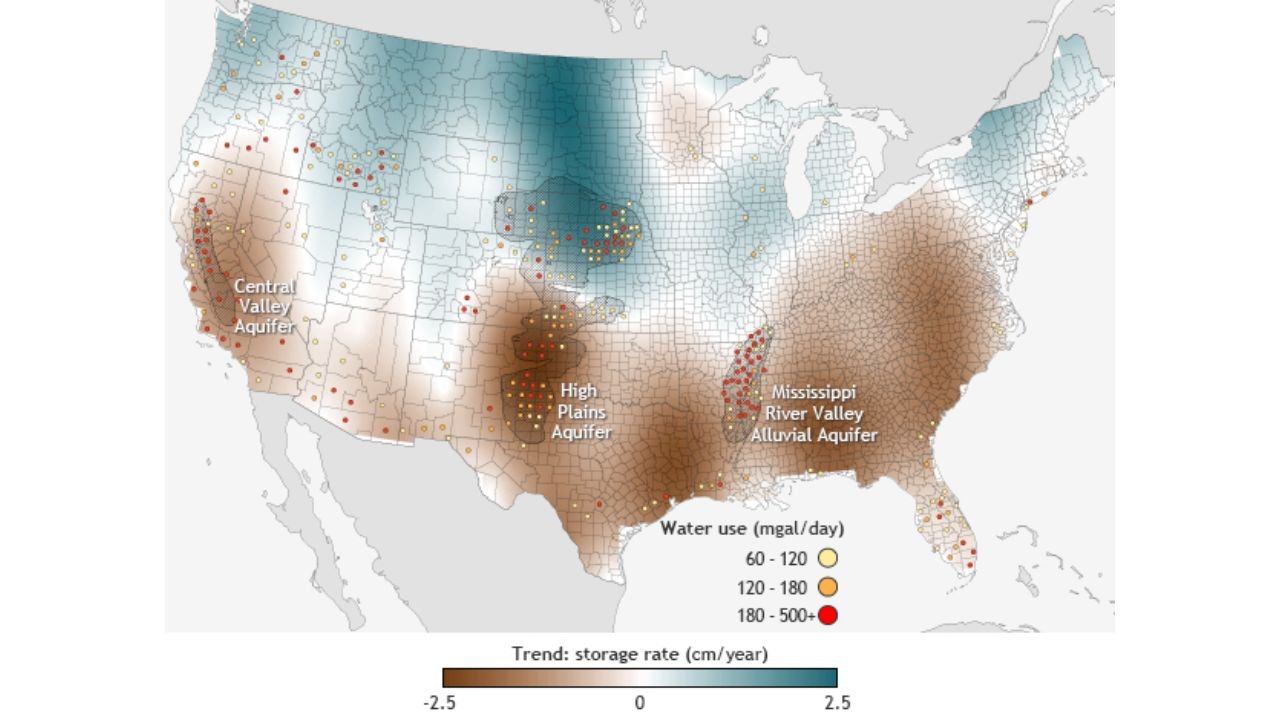

New data shows that the nation’s most productive agricultural areas — including the High Plains, the Midwest, and California’s Central Valley — are losing groundwater far faster than nature can replace it, while decades of soil degradation have weakened the land’s capacity to hold water at the surface.

Ogallala Aquifer Depletion Threatens the Heart of U.S. Irrigation

The Ogallala Aquifer, also known as the High Plains Aquifer, supports nearly 30 percent of all U.S. irrigation, making it one of the most critical water sources for American food production.

Since large-scale agricultural development began, the aquifer has lost an estimated 286 million acre-feet of water, equal to 93.2 trillion gallons. Portions of Kansas and Texas are now on pace to experience complete groundwater depletion within the next 20 to 50 years.

Natural recharge occurs at less than one inch per year, and scientists estimate that full replenishment would take up to 6,000 years, making current losses effectively permanent on human time scales.

Central Valley Groundwater Pumping Outpaces Recharge Fivefold

California’s Central Valley, which produces roughly 25 percent of the nation’s food supply, faces an equally alarming situation.

Groundwater is being pumped five times faster than it can naturally recharge, causing severe land subsidence. In some locations, the land has sunk by as much as 28 feet, permanently destroying aquifer storage capacity and reducing the region’s future water resilience.

Unlike temporary drought conditions, subsidence represents irreversible structural damage to underground water systems.

Loss of the Small Water Cycle Is Worsening Drought Impacts

Beyond groundwater depletion, researchers warn of a more subtle but potentially greater threat: the breakdown of the small water cycle, which governs how land captures, stores, and recycles rainfall.

The small water cycle relies on vegetation and soil biology to return moisture to the atmosphere through evapotranspiration, generating more than 50 percent of precipitation in most river basins.

This so-called “green water” accounts for four to five times more agricultural water use than the “blue water” drawn from rivers and aquifers. When soils are disturbed and left bare, this natural moisture recycling system fails.

Soil Degradation Is Reducing Water Storage Capacity

U.S. agricultural soils have lost approximately 50 percent of their original organic matter over the past century, dramatically reducing their ability to hold water.

Each 1 percent increase in organic matter allows soil to store an additional 20,000 gallons of water per acre. The widespread loss of three to four percentage points means many farms now retain tens of thousands fewer gallons per acre than they once did.

Bare soils can reach surface temperatures up to 24°C higher than vegetated areas, creating localized heat islands that repel rainfall, increase runoff, and eliminate evaporative cooling.

Conventional Farming Practices Accelerate the Decline

Modern agricultural practices often compound these problems. Excessive tillage collapses soil structure, while synthetic fertilizers accelerate organic matter decomposition. Pesticides disrupt soil microbiology, and heavy machinery compacts soil, reducing infiltration.

Together, these practices weaken soil aggregates, reduce porosity, and limit the land’s ability to absorb and store rainfall during storms.

Restoring the Small Water Cycle Offers Immediate Hope

While aquifer depletion may be irreversible, scientists say the small water cycle can be restored relatively quickly through regenerative farming practices.

Continuous living roots help maintain soil pore structure, while decaying roots create channels for infiltration. Healthy soil microbiomes produce biological glues that form water-stable aggregates, increasing both infiltration and storage.

Permanent soil cover reduces evaporation and prevents surface sealing. Studies show that five years of cover cropping can improve infiltration rates by up to 200 percent.

Integrated biological diversity — including crop rotations, livestock integration, and perennial systems — strengthens the feedback loops between soil carbon, water retention, and climate regulation.

Long-Term Water Security Depends on Soil Health

Experts warn that aquifer depletion cannot be undone, but rebuilding soil health offers a realistic path to restoring agricultural resilience.

By repairing the small water cycle, farms can increase water availability, reduce runoff, moderate temperatures, and improve drought resistance — all while maintaining food production in an increasingly uncertain climate.

What do you think — can restoring soil health slow America’s growing water crisis, or has groundwater depletion already gone too far? Share your thoughts and follow ongoing agricultural and environmental coverage at WaldronNews.com.